What Is Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus?

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, or NPH, is a neurological condition where too much cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up in the brain’s ventricles - the fluid-filled spaces inside the brain. Unlike other forms of hydrocephalus, the pressure doesn’t spike. It stays within the normal range of 70-245 mm H₂O, which is why it’s called “normal pressure.” Despite the name, this fluid buildup stretches the brain tissue and causes real, progressive damage.

NPH mostly affects people over 60. About 0.4% of adults over 65 have it, and that number jumps to nearly 6% in nursing home residents. It’s often mistaken for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or just “getting older.” But here’s the key difference: NPH is one of the few types of dementia that can be reversed with surgery.

The condition was first clearly described in 1965 by neurosurgeons Salomón Hakim and Raymond Adams. Since then, research has shown that up to 90% of properly selected patients improve after shunt surgery. Yet, because symptoms overlap with other brain disorders, up to 60% of cases go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

The Three Classic Signs: Gait, Cognition, and Bladder Control

NPH doesn’t show up with one symptom - it shows up with three, and they usually appear in a specific order:

- Gait disturbance - This is the first and most consistent sign. People walk slowly, with small, shuffling steps. Their feet seem stuck to the floor. They may turn with multiple small steps instead of one smooth turn. In studies, 100% of diagnosed NPH patients show this symptom. It’s often called a “magnetic gait” because it looks like their feet are glued to the ground.

- Cognitive impairment - Thinking slows down. Memory isn’t the main problem. Instead, people struggle with planning, paying attention, or starting tasks. They might forget why they walked into a room or have trouble following a conversation. Neuropsychological tests show frontal-subcortical deficits - meaning the brain’s “control center” for decision-making isn’t working right. About 73% of patients show this.

- Urinary incontinence - This comes last, and not everyone gets it. Only about one-third of patients experience it. But when it does happen, it’s often sudden and unexplained. It’s not caused by prostate issues or weak pelvic muscles - it’s the brain losing control of the bladder signal.

Here’s the catch: Only about 30% of people have all three symptoms at once. Many only have one or two. That’s why doctors miss it. If someone over 65 starts walking oddly and seems “slower in the head,” NPH should be on the list.

How Is NPH Diagnosed?

Diagnosing NPH isn’t just about looking at an MRI. It’s a process - and it takes time. Most patients wait an average of 14 months before getting the right diagnosis.

The first step is imaging. A CT scan or MRI will show enlarged ventricles. The key measurement is Evan’s index - the ratio of ventricle width to brain width. If it’s above 0.3, that’s a red flag. MRI can also show periventricular edema - fluid leaking around the ventricles - which is another strong indicator.

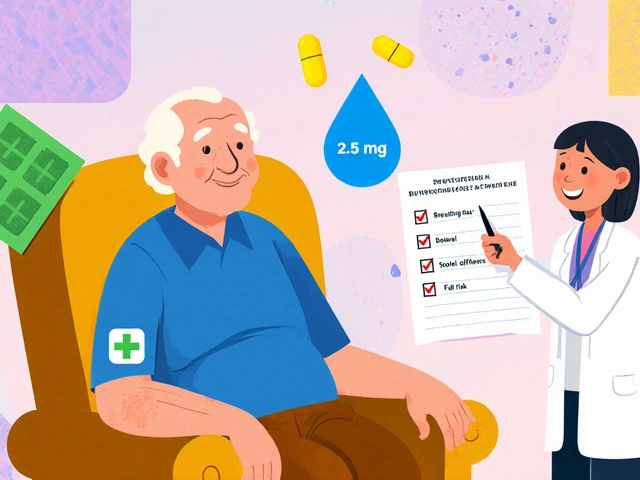

But imaging alone isn’t enough. You need to test how the brain responds to fluid removal. That’s where the CSF tap test comes in. A doctor removes 30-50 milliliters of spinal fluid with a needle in the lower back. Then, they measure the patient’s walking speed, balance, and mental clarity before and after.

If the person walks 10% faster or scores better on a memory test after the tap, there’s an 82% chance they’ll benefit from a shunt. A 15% improvement means they have nearly a 90% chance of success.

Other tests include:

- Neuropsychological testing - especially the Trail Making Test Part B and Digit Symbol Substitution Test

- CSF outflow resistance measurement - using newer tools like the Radionics® CSF Dynamics Analyzer

- External lumbar drainage - a 3-5 day test where fluid is drained continuously to see if symptoms improve

Doctors also rule out other conditions. Alzheimer’s shows memory loss first, not gait. Parkinson’s has tremors and stiffness. Vascular dementia follows strokes. NPH is different - it’s slow, steady, and potentially reversible.

Shunt Surgery: The Only Treatment

There’s no pill for NPH. The only treatment is surgery - a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt.

The procedure involves placing a thin tube (catheter) into the brain’s ventricle. That tube connects to a valve, usually placed behind the ear, which then runs down to the abdomen. The valve controls how much fluid drains - typically set between 50 and 200 mm H₂O. The fluid flows into the belly, where the body naturally absorbs it.

The surgery takes about 60-90 minutes under general anesthesia. Most people go home in 2-7 days. Recovery takes 6-12 weeks. But many notice changes within 48 hours.

One patient, a 72-year-old man, posted on a neurosurgery forum: “My 10-meter walk went from 28 seconds to 12 seconds in two days. I hadn’t been able to control my bladder in 18 months - it stopped the day after surgery.”

Success rates are high: 70-90% of well-selected patients improve. Gait improves in 76%, cognition in 62%, and bladder control in 58% after one year. Eighty-nine percent of patients say they’re satisfied with the outcome.

Why Shunts Sometimes Fail

Not every shunt works. About 20-30% of patients don’t improve after surgery. Why?

- Wrong diagnosis - If the patient has Alzheimer’s mixed with NPH (which happens in 25-30% of cases), the shunt won’t fix the Alzheimer’s part.

- Delayed treatment - If symptoms have been going on for more than a year, the brain may have already changed too much. Studies show that waiting past 12 months cuts surgical effectiveness by 30%.

- Shunt complications - Infections happen in about 8.5% of cases. Shunts can get blocked or leak. About 15% need revision within two years. Older patients (over 80) have higher infection rates - up to 21%.

- Incorrect valve settings - Too much drainage can cause headaches or bleeding in the brain. Too little, and symptoms don’t improve. Valve pressure often needs fine-tuning after surgery.

One woman shared her experience: “The tap test looked perfect. But after the shunt, my cognition didn’t get better. I got chronic headaches and had to have the valve adjusted twice.”

That’s why careful patient selection matters. Doctors now use tools like the iNPH Diagnostic Calculator app, which uses 12 clinical factors to predict shunt success with 85% accuracy.

Who Gets Treated - and Who Doesn’t

Not everyone with enlarged ventricles needs a shunt. The European Federation of Neurological Societies and the International Society for Hydrocephalus agree: surgery should only be offered to those who show clear signs of CSF-related symptoms and respond to the tap test.

Insurance coverage is a big hurdle. In the U.S., Medicare covers 85% of shunt surgeries, but diagnostic tests like lumbar punctures and external drainage are often denied. About 37% of patients face prior authorization rejections.

Shunt systems cost between $3,200 and $5,800. The main brands are Medtronic (Strata® valve), Codman (Hakim® valve), and Miethke. These are FDA-approved Class II devices. Newer programmable valves allow doctors to adjust pressure without another surgery - a big help for long-term management.

Meanwhile, researchers are working on better ways to diagnose NPH without invasive tests. Three clinical trials are testing blood and CSF biomarkers that could detect NPH with over 90% accuracy. If successful, they could cut diagnosis time from months to days.

Living With NPH - Before and After

Before treatment, many patients lose independence. They stop driving. They need help bathing or dressing. Caregivers burn out. Quality of life scores drop sharply.

After a successful shunt, things change fast. People walk without assistance. They remember appointments. They stay dry. One study showed a 28.5-point increase on the EQ-5D quality-of-life scale - that’s a massive jump.

But recovery isn’t instant. Physical therapy helps rebuild strength and balance. Occupational therapy helps with daily tasks. Families need to understand that improvement takes weeks, not days.

Long-term data from Sweden shows that 68% of patients still have better function 20 years after surgery. But shunts aren’t permanent. The average shunt lasts 6.3 years before needing repair or replacement.

What Comes Next?

NPH is no longer a mystery - it’s a solvable problem. But it still flies under the radar. Too many older adults are labeled as “just aging” when they might be suffering from a treatable condition.

If you or someone you know over 60 has:

- Walking differently - slow, shuffling, wide-based steps

- Forgetting how to do routine tasks

- Accidentally wetting themselves

- then ask for an evaluation. Get an MRI. Ask about a CSF tap test. Don’t wait.

The window for treatment is narrow, but it’s real. And for many, the difference between a shunt and no shunt is the difference between living at home - or in a nursing home.

Can normal pressure hydrocephalus be cured?

NPH can’t be cured permanently, but its symptoms can be reversed in most cases with shunt surgery. About 70-90% of patients see major improvement in walking, thinking, and bladder control. However, shunts can fail or need adjustments over time, and the condition requires lifelong monitoring.

Is NPH the same as Alzheimer’s?

No. Alzheimer’s primarily affects memory and language, with cognitive decline progressing slowly. NPH affects movement first - especially walking - and thinking is more about slow processing and lack of initiative. MRI patterns and CSF tap tests can tell them apart with 87% accuracy. Unlike Alzheimer’s, NPH is often treatable with surgery.

How do you test for NPH?

Testing starts with an MRI or CT scan to check for enlarged ventricles. Then, a CSF tap test is done: 30-50 mL of spinal fluid is removed, and walking speed and mental tests are measured before and after. If the person improves by 10% or more, they’re likely a good candidate for a shunt. Some centers also use external lumbar drainage for longer testing.

What are the risks of shunt surgery?

Risks include infection (about 8.5% of cases), shunt blockage (15% within two years), bleeding in the brain (5.7%), and over-drainage causing headaches. Older patients have higher infection rates. Shunts may need one or more revisions over time. But for most patients, the benefits outweigh the risks - especially when symptoms are caught early.

Can NPH be treated without surgery?

No. There are no medications that effectively treat NPH. Drugs used for Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s don’t help. The only proven treatment is surgical placement of a shunt to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid. Research into non-invasive treatments is ongoing, but nothing is approved yet.

How long does recovery take after shunt surgery?

Most patients notice improvement in walking within 48 hours. Full recovery - including cognitive and bladder control - can take 6 to 12 weeks. Physical therapy is often recommended to rebuild strength and balance. Regular follow-ups with a neurosurgeon are needed for the first 6 months to adjust the shunt valve if necessary.

Why is NPH often misdiagnosed?

Because its symptoms - slow walking, memory issues, incontinence - look exactly like normal aging or other brain diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. Many doctors don’t consider NPH unless it’s specifically suggested. Plus, diagnostic tests like the CSF tap aren’t always ordered due to insurance barriers or lack of awareness. As a result, up to 60% of cases go undetected.

Is NPH common?

Yes - and underdiagnosed. About 0.4% of people over 65 have NPH, and up to 5.9% of nursing home residents. That means tens of thousands of older adults in the U.S. alone could benefit from treatment. Yet, because it’s rarely considered, most never get tested.

November 14, 2025 AT 12:16 PM

This is the most goddamn important post I've read all year. I watched my dad waste away for two years thinking he was just 'getting old'-shuffling feet, forgetting where he put his keys, wetting himself at 3 a.m. No one even mentioned NPH until his neurologist finally did a tap test. Two weeks after the shunt? He was walking the dog again. No more diapers. No more 'I'm too tired' excuses. They call it dementia? Nah. It's a clogged drain. And we fix drains. Don't let them tell you it's just aging. It's not. It's treatable. Fight for the test.

November 15, 2025 AT 18:44 PM

Thank you for this incredibly clear breakdown. I've spent the last six months researching this after my mother's diagnosis, and the lack of awareness is staggering. The CSF tap test is not widely known outside neurology circles, and even some GPs dismiss gait changes as 'just arthritis.' The fact that 90% of properly selected patients improve is a miracle-yet so few get screened. I hope this post reaches every family doctor in the UK. It's not about age. It's about opportunity.

November 16, 2025 AT 11:09 AM

bro this is fake news i work in a hospital in delhi and no one here even knows what nph is. old people just get confused and wet their pants thats it. why waste money on shunts when you can give them chai and a blanket? also why do you need 3 tests when 1 mri is enough? you americans overcomplicate everything. also the word 'ventriculoperitoneal' sounds like a bad spell from harry potter.

November 17, 2025 AT 16:17 PM

While the statistics presented are compelling, I must question the methodology behind the 90% improvement rate. Were the patients rigorously screened for comorbidities? Were the outcome measures validated? The emotional language here-'reversible dementia'-is dangerously misleading. NPH is not a cure. It is a management strategy with significant risks. And the assumption that all gait changes in the elderly are NPH is a dangerous oversimplification.

November 18, 2025 AT 07:17 AM

My uncle had this. Didn't know what was going on until his wife pushed for the tap test. He went from barely walking to playing golf in three months. No magic pill. Just a tube and a valve. People think old folks are just slow. Nah. Sometimes they're just full of fluid. And that's fixable. Don't ignore the shuffle. It's not laziness. It's a warning.

November 19, 2025 AT 21:09 PM

shunt surgery saved my grandpa. he was stuck in a chair for 8 months. after the surgery he started making pancakes again. he didn't even remember he used to love them. the first time he made them he cried. i cried. it wasn't just about walking. it was about coming back. if your old relative is slow and forgetful and wetting themselves-ask for the tap test. it's not hard. it's not expensive. it's life changing.

November 20, 2025 AT 14:37 PM

Let’s be real. This is just a money grab. Shunts cost thousands. Insurance fights it. Hospitals push it. The real issue? We’re overtreating normal aging. You don’t need a shunt-you need a walker and a reminder app. The 90% success rate? Probably inflated by cherry-picked patients who were already borderline. This isn’t medicine. It’s marketing.

November 21, 2025 AT 20:20 PM

so i had this guy at work who was acting weird and i told him to get checked and he did and turns out he had nph and now he’s back to normal but like… why did no one else notice? everyone just thought he was being weird or lazy. this is wild. i’m telling my aunt to get tested. she’s been forgetting her meds and walking funny. she’s 71. she thinks it’s just stress. lol.

November 23, 2025 AT 13:49 PM

as someone from india, i want to say this is so important. in our villages, old people are left alone and called 'dumb' when they forget things. this post is a gift. i am sharing it with my cousins in rural uttar pradesh. we must tell our doctors: not every shuffle is old age. not every confusion is dementia. this is treatable. we must not let stigma silence the truth. thank you for writing this.

November 25, 2025 AT 00:35 AM

While the clinical data presented is robust, the absence of longitudinal neuroimaging correlation in the discussion of shunt efficacy is a notable omission. The periventricular hyperintensities on FLAIR sequences, particularly in the context of concomitant cerebral small vessel disease, significantly modulate surgical outcomes. Additionally, the reliance on the CSF tap test without concurrent intracranial pressure monitoring introduces selection bias. A multidisciplinary approach incorporating biomarker profiling (e.g., Aβ42, tau, neurofilament light chain) remains imperative for differential diagnosis.