When a pharmaceutical company spends $150 million to develop a drug for a disease that affects only 8,000 people in the U.S., it’s not a charity case-it’s a calculated bet. And the only thing making that bet possible is orphan drug exclusivity. This isn’t just a loophole. It’s a legal lifeline designed to keep rare-disease medicines from disappearing before they ever reach patients.

Before 1983, there were barely any treatments for rare diseases. The FDA defines a rare disease as one affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans. For companies, that’s a financial dead end. Even if the drug works perfectly, there aren’t enough patients to recoup the cost of research, clinical trials, and manufacturing. So, most big drugmakers ignored these conditions entirely. That changed when Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act in January 1983. Signed by President Reagan, the law didn’t just encourage development-it created a real economic model for it.

How Orphan Drug Exclusivity Works

Orphan drug exclusivity gives a company seven years of market protection in the U.S. starting the day the FDA approves the drug for its rare disease use. During that time, no other company can get approval for the same drug to treat the same condition-unless they prove their version is clinically superior. That means better effectiveness, fewer side effects, or a safer way to take it. The bar is high. Since 1983, only three cases have met this standard.

Here’s the key detail: exclusivity isn’t tied to a patent. It’s tied to the specific drug and the specific disease. So if a company gets approval for using Drug X to treat Disease Y, no one else can get approval for Drug X for Disease Y-even if they develop it independently. That’s different from patents, which protect the chemical structure or how the drug is made. Patents can expire. Exclusivity doesn’t. It runs from approval date to seven years later, no matter what.

It’s not a monopoly on the drug itself. If the same drug is approved for another condition-say, a common form of diabetes-the company still has to compete with generics for that use. But for the orphan use? It’s theirs alone.

Why This System Exists

The numbers tell the story. In the decade before the Orphan Drug Act, only 38 drugs were developed for rare diseases. Since 1983? Over 500. That’s a 13-fold increase. The reason? Exclusivity turned a losing proposition into a viable business.

Think about it: a company might spend $200 million to bring a drug to market for a disease affecting 15,000 people. Without exclusivity, generics would enter as soon as the patent expired. But with exclusivity, they can’t touch it for seven years. That’s enough time to build a customer base, establish pricing, and recover costs-even if the price is high.

It’s not perfect. Some companies have used the system to extend protection for drugs already profitable in other markets. Humira, for example, received multiple orphan designations even though its main use is for common autoimmune diseases. Critics argue this stretches the intent of the law. But for most small biotech firms, this protection is the only reason they can exist.

How It Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. isn’t alone. The European Union gives orphan drugs ten years of exclusivity-three years longer than the U.S. But the EU also has more flexibility. If a company completes pediatric studies, they can get an extra two years. And under certain conditions, the exclusivity can be cut from ten to six years if the drug becomes too profitable. The U.S. doesn’t have those adjustments. It’s a fixed seven-year clock.

That difference matters. European regulators are now considering whether to lower the standard period to eight years, especially for drugs that end up selling well beyond the rare disease market. The U.S. hasn’t made any changes yet. For now, seven years remains the rule.

The Real-World Impact

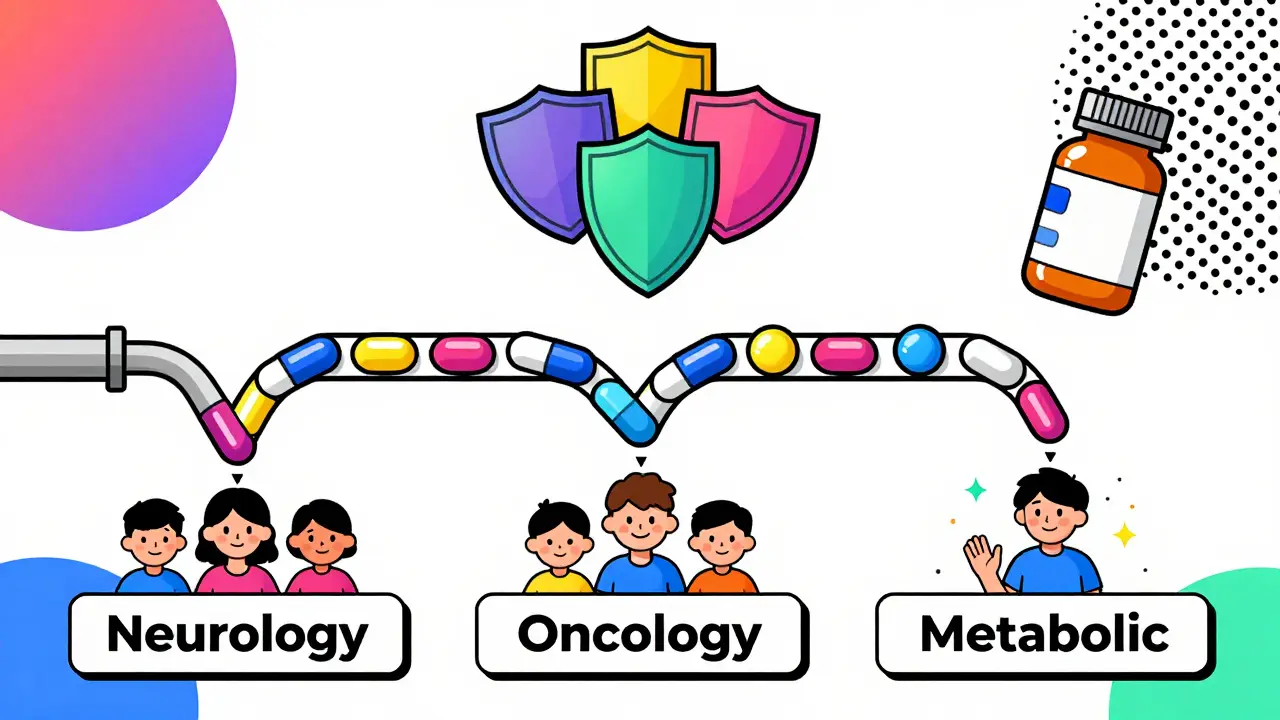

By 2022, orphan drugs made up 24.3% of global prescription sales-$217 billion. That’s up from 16.1% in 2018. Oncology leads the way, accounting for nearly half of all orphan approvals. But neurology, hematology, and metabolic disorders are growing fast. The top 10 orphan drugs brought in $95 billion in 2022. And 72% of new drugs approved by the FDA in 2023 had an orphan designation. That’s up from 51% in 2018.

For patients, this means more options. In 2023 alone, the FDA granted 434 orphan designations-the highest number ever. Conditions once considered untreatable now have drugs on the market. A child with a rare genetic disorder might now have a daily pill instead of lifelong hospital visits. That’s the goal.

But it’s not all progress. The same system that helps small companies also lets big ones game the system. Some companies file for multiple orphan designations for the same drug across different diseases-what experts call “salami slicing.” One drug might have five orphan labels, each giving seven years of protection. That’s not the intent, but it’s legal.

What Sponsors Need to Know

If you’re developing a drug for a rare disease, timing matters. Apply for orphan designation as early as possible-ideally during Phase 1 or early Phase 2 trials. The FDA reviews these applications in about 90 days and approves 95% of them if the disease meets the 200,000-person threshold. But you can’t wait until approval to apply. The clock on exclusivity starts at approval, not designation. So if you delay, you lose time.

You also need to prove the disease is rare. That means solid epidemiological data-not just estimates. The FDA requires population studies, medical records, and sometimes even global prevalence data. A weak case gets rejected. And if another company gets approval first? You lose the exclusivity. It’s a race. Many companies apply for the same indication. Only the first to market wins.

And don’t assume exclusivity protects everything. If your drug is approved for both an orphan and a common disease, generics can enter the market for the common use. You only get protection for the rare disease indication.

What’s Next?

There’s growing pressure to reform the system. In May 2023, the FDA released draft guidance to clarify what counts as the “same drug,” especially after controversial cases like Ruzurgi. The goal? Stop companies from using orphan status to block competition when the drug already has a big market.

Some lawmakers want to require proof of “unmet medical need”-not just low patient numbers. Others want to cap how many orphan designations one drug can get. But for now, the system stays. And it’s working. Nine out of ten biopharma companies say orphan exclusivity is critical to their rare disease pipelines.

The truth is simple: without this protection, most rare-disease drugs wouldn’t exist. Patients wouldn’t have treatments. Companies wouldn’t take the risk. It’s not a perfect system. But it’s the only one we have-and it’s saved lives.

How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts seven years from the date the FDA approves the drug for its rare disease indication. This period begins at approval, not at the time of orphan designation, and it runs independently of patent protection.

Can another company make the same drug for the same rare disease?

No-not during the seven-year exclusivity period. The FDA will not approve another company’s application for the same drug to treat the same rare disease unless that company proves clinical superiority. That means showing their version offers a substantial therapeutic advantage, like better effectiveness, fewer side effects, or a safer delivery method. Only three cases have met this standard since 1983.

Does orphan exclusivity replace patent protection?

No. Orphan exclusivity and patent protection are separate. Patents protect the chemical compound or how the drug is made, while orphan exclusivity protects the drug for a specific rare disease use. Most drugs rely on patents for longer-term protection. In fact, orphan exclusivity was the main reason for delayed generic entry in only 12% of cases, according to IQVIA. Patents remain the dominant form of market protection.

Can a drug have multiple orphan designations?

Yes. A single drug can receive orphan designation for multiple rare diseases. Each designation comes with its own seven-year exclusivity period. For example, if a drug is approved for Disease A and later for Disease B, it gets seven years of protection for each condition. This practice, sometimes called "salami slicing," is legal but controversial.

What happens if a drug is approved for both an orphan and a common disease?

The orphan exclusivity only protects the rare disease use. For the common disease indication, other companies can still develop and sell generic versions once the patent expires. So a drug might have exclusive rights for treating a rare condition but face generic competition for its other uses.

How do companies apply for orphan drug designation?

Companies submit a request to the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development, typically during early clinical development. The application must prove the disease affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. and that the drug shows promise for treating it. The FDA reviews applications in about 90 days and approves 95% of well-prepared submissions.